The Building

Callie’s building witnessed a rich history. It was built in the 1870s, during the great industrialization process, and it was a machine factory for more than fifty years. Over the course of the the 20th century it was home to a wide assortment of companies before entering into a period of disuse that began in the 1990s and lasted over 20 years. Learn more about the building’s history as well as the renovation process below.

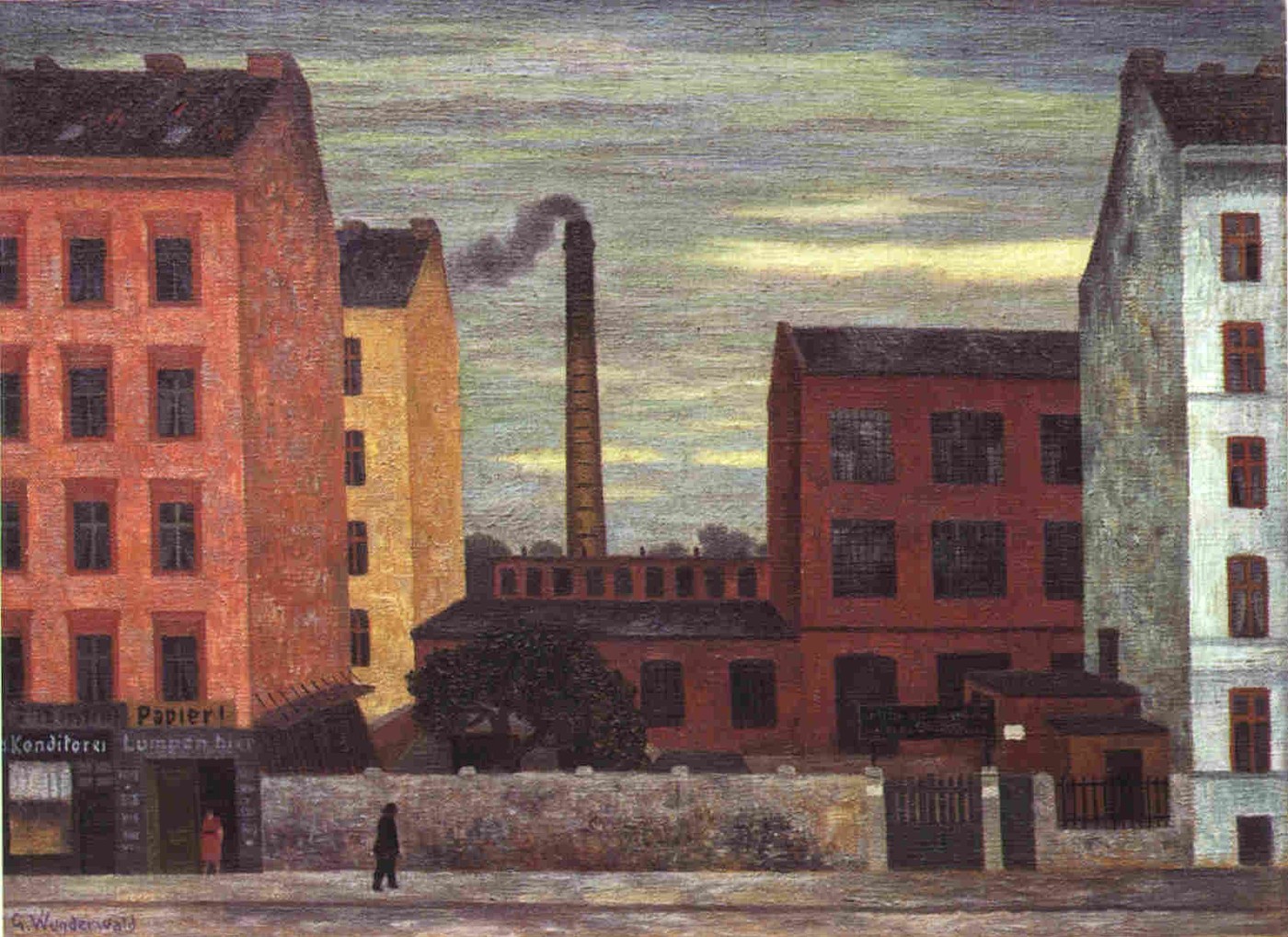

Gustav Wunderwald, Fabrik an der Lindower Strasse, Berlin N, 1927 Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz – Museum Gunzenhauser, property of the Gunzenhauser Foundation. Photo by archive.

History of Lindower Straße 20-22

Beginnings: Max Hasse & Comp. machine factory

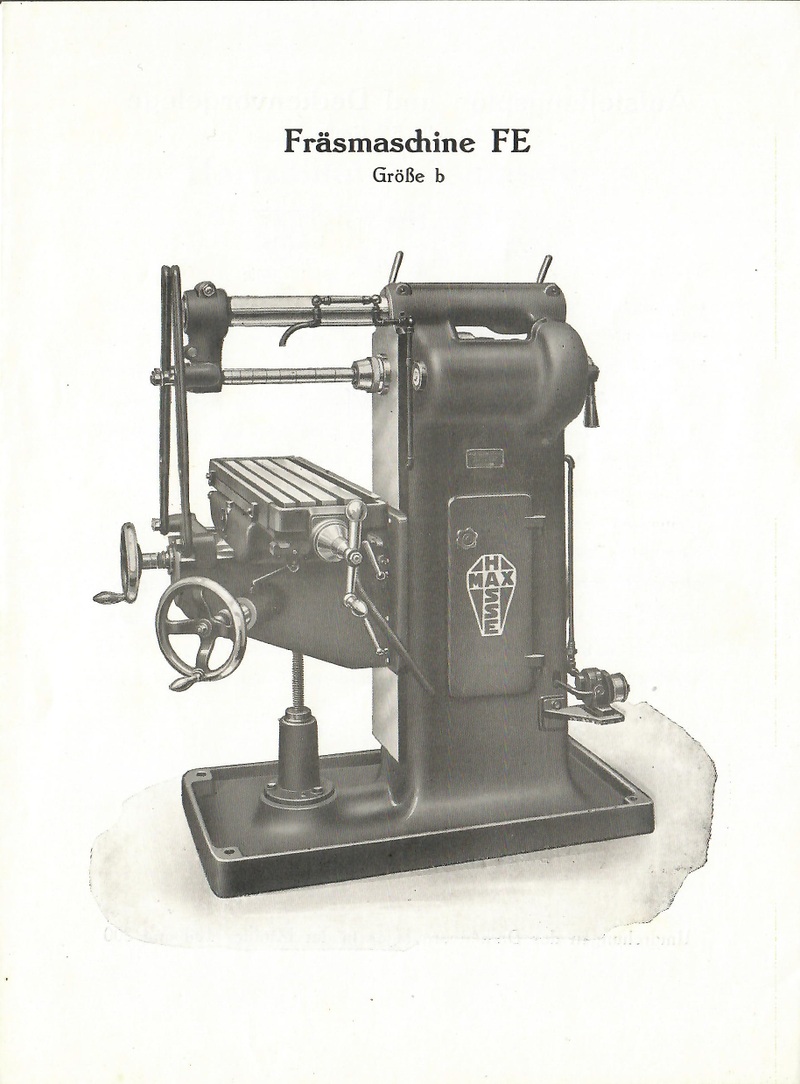

The Max Hasse & Comp. Machine Factory was built in 1871 by August and Max Hasse and was registered as the “Mechanical Engineering Institute for American Machines”. The factory produced a variety of different apparatuses that could standardize production, including milling, riveting and sewing machines based on American innovations of the time. 1870 marked the beginning of the Second Industrial Revolution, or Technological Revolution, and advancements in production were exponential. The 1880s saw electricity come to Berlin: the first lightbulb, powerplant, and electric tram all emerged in a single decade. By 1896, construction began on the the U-Bahn, the underground rail system.

View of a production space in the Lindower Strasse 20-22. Photo by Deutsches Technikmuseum archive.

It was around 1900, after Max Hasse’s death, that his widow Anna Hasse gained ownership over the company.

The following decades saw massive upheaval in Berlin. Wartime Germany saw rationing and low supplies of food, coal, and other essentials. Following the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Germany entered into a period of economic instability and severe inflation. In 1924, during the Weimar Republic, the fiscal situation began to improve, but many businesses had already suffered irreparably.

In 1929, after years of low profitability, the manufacturing rights of Max Hasse & Comp. were sold to another major Berlin-based machine factory, Niles Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH (liscensee of the American machine tool manufacturer “Niles Tool Works Company” based in Hamilton, Ohio). With this transaction, the machine production in Lindower Strasse 20-22 ceased.

Title page of a product brochure with a milling machine by Max Hasse, year unknown.

From the 1930s until the fall of the Berlin Wall

A large number of businesses and manufacturers took up residence on the premises of Lindower Strasse 20-22 at the beginning of the 1930s.

One of the first companies to settle into the premises were the household goods manufacturers Graetz & Glückstein. Founded in 1926, the company was expropriated by the Nazis in 1937, as were the majority of Jewish-owned businesses in Berlin.

Entry of the company Bode Panzer in the industry directory for Berlin 1946/47.

In around 1932, the famous Bode-Panzer safe factories took up residence in Lindower Strasse 20-22. Founded in 1858 by Louis Bode and Heinrich Troue in Hannover as the company Bode & Troue, it was the first German factory to produce safes and armoured cash boxes as well as fire and burglar proof steel vaults. In 1924, the company had merged with Panzer AG Berlin, founded in 1898, to form Bode Panzer AG. The previous Panzer AG Berlin had built the vault of the Berlin coin cabinet at the Bode-Museum (formerly Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum) from about 1900 to 1904 and continued to be a leading supplier of safes and vaults in the subsequent decades.

In addition to household goods and safes, Lindower Strasse 20-22 housed a broad assortment of companies over the years. Among them were a button factory, a quartz lamp factory, bookbinders, a liqueur manufacturer, as well as the service clothing manufacturers Tofaute & Gronwald, who later produced the uniforms of the West German Police.

2011-2016: the renovation process

After years of interim use—among other things as part of the Mica Moca art project in summer 2011—structural renovation began in 2013. The project was conceptualized by ASA studio albanese, Vicenza/Milano, and overseen by Heim Balp Architekten, Berlin.

A two-story extension was added to the rooftop. Covered in reflective metal cladding, the extension is visible but minimally alters the profile and proportions of the original building; at certain times of day, it reflects the sky and seems to disappear entirely.

The building before renovation. Photo by Nick Ash.

Throughout the renovation process, the brick building retained most of its details; only necessary structural changes were made, such as the addition of reinforced concrete wall supports where the building was no longer sound. All interventions were made evident by the use of simple but functional materials.

Many aspects of the building still correspond to their historical conditions, including the windows on the ground floor, the majority of the walls throughout the building, the freight elevator, as well as many of the cement floors.

While the side staircases were reinforced but left in their original state, the central stairway had to be replaced. The modern concrete intervention provides the public entrance with heightened functionality and safety.

View of the building after the renovation. Photo by Nick Ash.

The building today

The light-flooded spaces where machines used to be manufactured now provide room for all forms of artistic practice.

Callie’s has altered very little on the premises. A vertical shaft of unused space on the far side of the building was captured and transformed into three micro-apartments for international and visiting artists.

You can find out more about our current facilities here.